This cheat sheet is focused on providing developers with concentrated guidance on building application logging mechanisms, especially related to security logging.

Many systems enable network device, operating system, web server, mail server and database server logging, but often custom application event logging is missing, disabled or poorly configured. It provides much greater insight than infrastructure logging alone. Web application (e.g. web site or web service) logging is much more than having web server logs enabled (e.g. using Extended Log File Format).

Application logging should be consistent within the application, consistent across an organization's application portfolio and use industry standards where relevant, so the logged event data can be consumed, correlated, analyzed and managed by a wide variety of systems.

Application logging should always be included for security events. Application logs are invaluable data for:

- Identifying security incidents

- Monitoring policy violations

- Establishing baselines

- Assisting non-repudiation controls (note that the trait non-repudiation is hard to achieve for logs because their trustworthiness is often just based on the logging party being audited properly while mechanisms like digital signatures are hard to utilize here)

- Providing information about problems and unusual conditions

- Contributing additional application-specific data for incident investigation which is lacking in other log sources

- Helping defend against vulnerability identification and exploitation through attack detection

Application logging might also be used to record other types of events too such as:

- Security events

- Business process monitoring e.g. sales process abandonment, transactions, connections

- Anti-automation monitoring

- Audit trails e.g. data addition, modification and deletion, data exports

- Performance monitoring e.g. data load time, page timeouts

- Compliance monitoring

- Data for subsequent requests for information e.g. data subject access, freedom of information, litigation, police and other regulatory investigations

- Legally sanctioned interception of data e.g. application-layer wire-tapping

- Other business-specific requirements

Process monitoring, audit, and transaction logs/trails etc. are usually collected for different purposes than security event logging, and this often means they should be kept separate.

The types of events and details collected will tend to be different.

For example a PCIDSS audit log will contain a chronological record of activities to provide an independently verifiable trail that permits reconstruction, review and examination to determine the original sequence of attributable transactions. It is important not to log too much, or too little.

Use knowledge of the intended purposes to guide what, when and how much. The remainder of this cheat sheet primarily discusses security event logging.

The application itself has access to a wide range of information events that should be used to generate log entries. Thus, the primary event data source is the application code itself.

The application has the most information about the user (e.g. identity, roles, permissions) and the context of the event (target, action, outcomes), and often this data is not available to either infrastructure devices, or even closely-related applications.

Other sources of information about application usage that could also be considered are:

- Client software e.g. actions on desktop software and mobile devices in local logs or using messaging technologies, JavaScript exception handler via Ajax, web browser such as using Content Security Policy (CSP) reporting mechanism

- Embedded instrumentation code

- Network firewalls

- Network and host intrusion detection systems (NIDS and HIDS)

- Closely-related applications e.g. filters built into web server software, web server URL redirects/rewrites to scripted custom error pages and handlers

- Application firewalls e.g. filters, guards, XML gateways, database firewalls, web application firewalls (WAFs)

- Database applications e.g. automatic audit trails, trigger-based actions

- Reputation monitoring services e.g. uptime or malware monitoring

- Other applications e.g. fraud monitoring, CRM

- Operating system e.g. mobile platform

The degree of confidence in the event information has to be considered when including event data from systems in a different trust zone. Data may be missing, modified, forged, replayed and could be malicious – it must always be treated as untrusted data.

Consider how the source can be verified, and how integrity and non-repudiation can be enforced.

Applications commonly write event log data to the file system or a database (SQL or NoSQL). Applications installed on desktops and on mobile devices may use local storage and local databases, as well as sending data to remote storage.

Your selected framework may limit the available choices. All types of applications may send event data to remote systems (instead of or as well as more local storage).

This could be a centralized log collection and management system (e.g. SIEM or SEM) or another application elsewhere. Consider whether the application can simply send its event stream, unbuffered, to stdout, for management by the execution environment.

- When using the file system, it is preferable to use a separate partition than those used by the operating system, other application files and user generated content

- For file-based logs, apply strict permissions concerning which users can access the directories, and the permissions of files within the directories

- In web applications, the logs should not be exposed in web-accessible locations, and if done so, should have restricted access and be configured with a plain text MIME type (not HTML)

- When using a database, it is preferable to utilize a separate database account that is only used for writing log data and which has very restrictive database, table, function and command permissions

- Use standard formats over secure protocols to record and send event data, or log files, to other systems e.g. Common Log File System (CLFS) or Common Event Format (CEF) over syslog; standard formats facilitate integration with centralised logging services

Consider separate files/tables for extended event information such as error stack traces or a record of HTTP request and response headers and bodies.

The level and content of security monitoring, alerting, and reporting needs to be set during the requirements and design stage of projects, and should be proportionate to the information security risks. This can then be used to define what should be logged.

There is no one size fits all solution, and a blind checklist approach can lead to unnecessary "alarm fog" that means real problems go undetected.

Where possible, always log:

- Input validation failures e.g. protocol violations, unacceptable encodings, invalid parameter names and values

- Output validation failures e.g. database record set mismatch, invalid data encoding

- Authentication successes and failures

- Authorization (access control) failures

- Session management failures e.g. cookie session identification value modification or suspicious JWT validation failures

- Application errors and system events e.g. syntax and runtime errors, connectivity problems, performance issues, third party service error messages, file system errors, file upload virus detection, configuration changes

- Application and related systems start-ups and shut-downs, and logging initialization (starting, stopping or pausing)

- Use of higher-risk functionality including:

- User administration actions such as addition or deletion of users, changes to privileges, assigning users to tokens, adding or deleting tokens

- Use of systems administrative privileges or access by application administrators including all actions by those users

- Use of default or shared accounts or a "break-glass" account.

- Access to sensitive data such as payment cardholder data,

- Encryption activities such as use or rotation of cryptographic keys

- Creation and deletion of system-level objects

- Data import and export including screen-based reports

- Submission and processing of user-generated content - especially file uploads

- Deserialization failures

- Network connections and associated failures such as backend TLS failures (including certificate validation failures), or requests with an unexpected HTTP verb

- Legal and other opt-ins e.g. permissions for mobile phone capabilities, terms of use, terms & conditions, personal data usage consent, permission to receive marketing communications

- Suspicious business logic activities such as:

- Attempts to perform a set actions out of order/bypass flow control

- Actions which don't make sense in the business context

- Attempts to exceed limitations for particular actions

Optionally consider if the following events can be logged and whether it is desirable information:

- Sequencing failure

- Excessive use

- Data changes

- Fraud and other criminal activities

- Suspicious, unacceptable, or unexpected behavior

- Modifications to configuration

- Application code file and/or memory changes

Each log entry needs to include sufficient information for the intended subsequent monitoring and analysis. It could be full content data, but is more likely to be an extract or just summary properties.

The application logs must record "when, where, who and what" for each event.

The properties for these will be different depending on the architecture, class of application and host system/device, but often include the following:

- When

- Log date and time (international format)

- Event date and time - the event timestamp may be different to the time of logging e.g. server logging where the client application is hosted on remote device that is only periodically or intermittently online

- Interaction identifier

Note A

- Where

- Application identifier e.g. name and version

- Application address e.g. cluster/hostname or server IPv4 or IPv6 address and port number, workstation identity, local device identifier

- Service e.g. name and protocol

- Geolocation

- Window/form/page e.g. entry point URL and HTTP method for a web application, dialogue box name

- Code location e.g. script name, module name

- Who (human or machine user)

- Source address e.g. user's device/machine identifier, user's IP address, cell/RF tower ID, mobile telephone number

- User identity (if authenticated or otherwise known) e.g. user database table primary key value, user name, license number

- What

- Type of event

Note B - Severity of event

Note Be.g.{0=emergency, 1=alert, ..., 7=debug}, {fatal, error, warning, info, debug, trace} - Security relevant event flag (if the logs contain non-security event data too)

- Description

- Type of event

Additionally consider recording:

- Secondary time source (e.g. GPS) event date and time

- Action - original intended purpose of the request e.g. Log in, Refresh session ID, Log out, Update profile

- Object e.g. the affected component or other object (user account, data resource, file) e.g. URL, Session ID, User account, File

- Result status - whether the ACTION aimed at the OBJECT was successful e.g. Success, Fail, Defer

- Reason - why the status above occurred e.g. User not authenticated in database check ..., Incorrect credentials

- HTTP Status Code (web applications only) - the status code returned to the user (often 200 or 301)

- Request HTTP headers or HTTP User Agent (web applications only)

- User type classification e.g. public, authenticated user, CMS user, search engine, authorized penetration tester, uptime monitor (see "Data to exclude" below)

- Analytical confidence in the event detection

Note Be.g. low, medium, high or a numeric value - Responses seen by the user and/or taken by the application e.g. status code, custom text messages, session termination, administrator alerts

- Extended details e.g. stack trace, system error messages, debug information, HTTP request body, HTTP response headers and body

- Internal classifications e.g. responsibility, compliance references

- External classifications e.g. NIST Security Content Automation Protocol (SCAP), Mitre Common Attack Pattern Enumeration and Classification (CAPEC)

For more information on these, see the "other" related articles listed at the end, especially the comprehensive article by Anton Chuvakin and Gunnar Peterson.

Note A: The "Interaction identifier" is a method of linking all (relevant) events for a single user interaction (e.g. desktop application form submission, web page request, mobile app button click, web service call). The application knows all these events relate to the same interaction, and this should be recorded instead of losing the information and forcing subsequent correlation techniques to re-construct the separate events. For example, a single SOAP request may have multiple input validation failures and they may span a small range of times. As another example, an output validation failure may occur much later than the input submission for a long-running "saga request" submitted by the application to a database server.

Note B: Each organisation should ensure it has a consistent, and documented, approach to classification of events (type, confidence, severity), the syntax of descriptions, and field lengths and data types including the format used for dates/times.

Never log data unless it is legally sanctioned. For example, intercepting some communications, monitoring employees, and collecting some data without consent may all be illegal.

Never exclude any events from "known" users such as other internal systems, "trusted" third parties, search engine robots, uptime/process and other remote monitoring systems, pen testers, auditors. However, you may want to include a classification flag for each of these in the recorded data.

The following should usually not be recorded directly in the logs, but instead should be removed, masked, sanitized, hashed, or encrypted:

- Application source code

- Session identification values (consider replacing with a hashed value if needed to track session specific events)

- Access tokens

- Sensitive personal data and some forms of personally identifiable information (PII) e.g. health, government identifiers, vulnerable people

- Authentication passwords

- Database connection strings

- Encryption keys and other primary secrets

- Bank account or payment card holder data

- Data of a higher security classification than the logging system is allowed to store

- Commercially-sensitive information

- Information it is illegal to collect in the relevant jurisdictions

- Information a user has opted out of collection, or not consented to e.g. use of do not track, or where consent to collect has expired

Sometimes the following data can also exist, and whilst useful for subsequent investigation, it may also need to be treated in some special manner before the event is recorded:

- File paths

- Database connection strings

- Internal network names and addresses

- Non sensitive personal data (e.g. personal names, telephone numbers, email addresses)

Consider using personal data de-identification techniques such as deletion, scrambling or pseudonymization of direct and indirect identifiers where the individual's identity is not required, or the risk is considered too great.

In some systems, sanitization can be undertaken post log collection, and prior to log display.

It may be desirable to be able to alter the level of logging (type of events based on severity or threat level, amount of detail recorded). If this is implemented, ensure that:

- The default level must provide sufficient detail for business needs

- It should not be possible to completely deactivate application logging or logging of events that are necessary for compliance requirements

- Alterations to the level/extent of logging must be intrinsic to the application (e.g. undertaken automatically by the application based on an approved algorithm) or follow change management processes (e.g. changes to configuration data, modification of source code)

- The logging level must be verified periodically

If your development framework supports suitable logging mechanisms, use or build upon that. Otherwise, implement an application-wide log handler which can be called from other modules/components.

Document the interface referencing the organisation-specific event classification and description syntax requirements.

If possible create this log handler as a standard module that can be thoroughly tested, deployed in multiple applications, and added to a list of approved and recommended modules.

- Perform input validation on event data from other trust zones to ensure it is in the correct format (and consider alerting and not logging if there is an input validation failure)

- Perform sanitization on all event data to prevent log injection attacks e.g. carriage return (CR), line feed (LF) and delimiter characters (and optionally to remove sensitive data)

- Encode data correctly for the output (logged) format

- If writing to databases, read, understand, and apply the SQL injection cheat sheet

- Ensure failures in the logging processes/systems do not prevent the application from otherwise running or allow information leakage

- Synchronize time across all servers and devices

Note C

Note C: This is not always possible where the application is running on a device under some other party's control (e.g. on an individual's mobile phone, on a remote customer's workstation which is on another corporate network). In these cases, attempt to measure the time offset, or record a confidence level in the event timestamp.

Where possible, record data in a standard format, or at least ensure it can be exported/broadcast using an industry-standard format.

In some cases, events may be relayed or collected together in intermediate points. In the latter some data may be aggregated or summarized before forwarding on to a central repository and analysis system.

Logging functionality and systems must be included in code review, application testing and security verification processes:

- Ensure the logging is working correctly and as specified

- Check that events are being classified consistently and the field names, types and lengths are correctly defined to an agreed standard

- Ensure logging is implemented and enabled during application security, fuzz, penetration, and performance testing

- Test the mechanisms are not susceptible to injection attacks

- Ensure there are no unwanted side-effects when logging occurs

- Check the effect on the logging mechanisms when external network connectivity is lost (if this is usually required)

- Ensure logging cannot be used to deplete system resources, for example by filling up disk space or exceeding database transaction log space, leading to denial of service

- Test the effect on the application of logging failures such as simulated database connectivity loss, lack of file system space, missing write permissions to the file system, and runtime errors in the logging module itself

- Verify access controls on the event log data

- If log data is utilized in any action against users (e.g. blocking access, account lock-out), ensure this cannot be used to cause denial of service (DoS) of other users

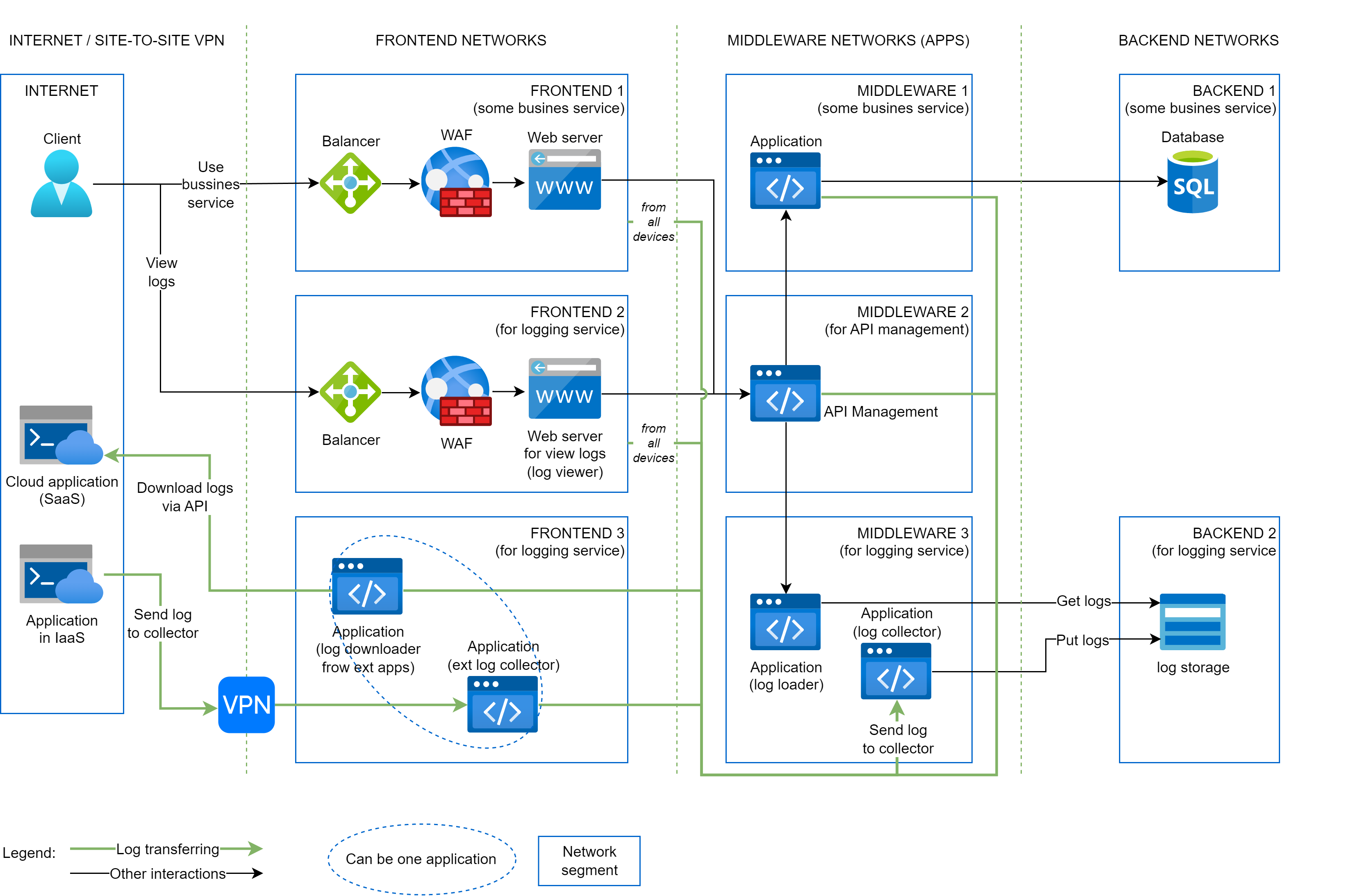

As an example, the diagram below shows a service that provides business functionality to customers. We recommend creating a centralized system for collecting logs. There may be many such services, but all of them must securely collect logs in a centralized system.

Applications of this business service are located in network segments:

- FRONTEND 1 aka DMZ (UI)

- MIDDLEWARE 1 (business application - service core)

- BACKEND 1 (service database)

The service responsible for collecting IT events, including security events, is located in the following segments:

- BACKEND 2 (log storage)

- MIDDLEWARE 3 - 2 applications:

- log loader application that download log from storage, pre-processes, and transfer to UI

- log collector that accepts logs from business applications, other infrastructure, cloud applications and saves in log storage

- FRONTEND 2 (UI for viewing business service event logs)

- FRONTEND 3 (applications that receive logs from cloud applications and transfer logs to log collector)

- It is allowed to combine the functionality of two applications in one

For example, all external requests from users go through the API management service, see application in MIDDLEWARE 2 segment.

As you can see in the image above, at the network level, the processes of saving and downloading logs require opening different network accesses (ports), arrows are highlighted in different colors. Also, saving and downloading are performed by different applications.

Full network segmentation cheat sheet by sergiomarotco: link

- Provide security configuration information by adding details about the logging mechanisms to release documentation

- Brief the application/process owner about the application logging mechanisms

- Ensure the outputs of the monitoring (see below) are integrated with incident response processes

Enable processes to detect whether logging has stopped, and to identify tampering or unauthorized access and deletion (see protection below).

The logging mechanisms and collected event data must be protected from mis-use such as tampering in transit, and unauthorized access, modification and deletion once stored. Logs may contain personal and other sensitive information, or the data may contain information regarding the application's code and logic.

In addition, the collected information in the logs may itself have business value (to competitors, gossip-mongers, journalists and activists) such as allowing the estimate of revenues, or providing performance information about employees.

This data may be held on end devices, at intermediate points, in centralized repositories and in archives and backups.

Consider whether parts of the data may need to be excluded, masked, sanitized, hashed, or encrypted during examination or extraction.

At rest:

- Build in tamper detection so you know if a record has been modified or deleted

- Store or copy log data to read-only media as soon as possible

- All access to the logs must be recorded and monitored (and may need prior approval)

- The privileges to read log data should be restricted and reviewed periodically

In transit:

- If log data is sent over untrusted networks (e.g. for collection, for dispatch elsewhere, for analysis, for reporting), use a secure transmission protocol

- Consider whether the origin of the event data needs to be verified

- Perform due diligence checks (regulatory and security) before sending event data to third parties

See NIST SP 800-92 Guide to Computer Security Log Management for more guidance.

The logged event data needs to be available to review and there are processes in place for appropriate monitoring, alerting, and reporting:

- Incorporate the application logging into any existing log management systems/infrastructure e.g. centralized logging and analysis systems

- Ensure event information is available to appropriate teams

- Enable alerting and signal the responsible teams about more serious events immediately

- Share relevant event information with other detection systems, to related organizations and centralized intelligence gathering/sharing systems

Log data, temporary debug logs, and backups/copies/extractions, must not be destroyed before the duration of the required data retention period, and must not be kept beyond this time.

Legal, regulatory and contractual obligations may impact on these periods.

Because of their usefulness as a defense, logs may be a target of attacks. See also OWASP Log Injection and CWE-117.

Who should be able to read what? A confidentiality attack enables an unauthorized party to access sensitive information stored in logs.

- Logs contain PII of users. Attackers gather PII, then either release it or use it as a stepping stone for further attacks on those users.

- Logs contain technical secrets such as passwords. Attackers use it as a stepping stone for deeper attacks.

Which information should be modifiable by whom?

- An attacker with read access to a log uses it to exfiltrate secrets.

- An attack leverages logs to connect with exploitable facets of logging platforms, such as sending in a payload over syslog in order to cause an out-of-bounds write.

What downtime is acceptable?

- An attacker floods log files in order to exhaust disk space available for non-logging facets of system functioning. For example, the same disk used for log files might be used for SQL storage of application data.

- An attacker floods log files in order to exhaust disk space available for further logging.

- An attacker uses one log entry to destroy other log entries.

- An attacker leverages poor performance of logging code to reduce application performance

Who is responsible for harm?

- An attacker prevent writes in order to cover their tracks.

- An attacker prevent damages the log in order to cover their tracks.

- An attacker causes the wrong identity to be logged in order to conceal the responsible party.

- OWASP ESAPI Documentation.

- OWASP Logging Project.

- IETF syslog protocol.

- Mitre Common Event Expression (CEE) (as of 2014 no longer actively developed).

- NIST SP 800-92 Guide to Computer Security Log Management.

- PCISSC PCI DSS v2.0 Requirement 10 and PA-DSS v2.0 Requirement 4.

- W3C Extended Log File Format.

- Other Build Visibility In, Richard Bejtlich, TaoSecurity blog.

- Other Common Event Format (CEF), Arcsight.

- Other Log Event Extended Format (LEEF), IBM.

- Other Common Log File System (CLFS), Microsoft.

- Other Building Secure Applications: Consistent Logging, Rohit Sethi & Nish Bhalla, Symantec Connect.