Focussing on problems is what helps us to do the least work possible to meet the needs of users. If we really understand users’ problem and are usefully agnostic about solutions then we can be flexible enough to always do the least work possible to meet our users’ needs.

Identifying a problem is not sufficient, we need to make sure that it’s a problem worth solving for our users. As product managers, we need to help our teams continually ask these questions about the problem we want to solve:

- Is it pervasive? Who specifically has the problem and does it affect lots of people?

- Is it urgent? Do those people need the problem to be solved right away or can they wait?

- Is it complex? Are people able to solve the problem for themselves or do they need someone else to solve it for them?

- Is it valuable for users? How painful is the problem for them and would they be willing to change their behaviour and use a new or different solution?

- Is it valuable for your organisation? Will solving the problem save more money than it costs to build the solution?

We have a compelling problem when you can answer ‘yes’ to all of these questions.

We are likely to reframe our problem several times during the product lifecycle and may even change our primary user. This is important and valuable as we refine the scope of our problem to be feasible to solve. We’ll often find that we start with a massive problem space and refine this to something with a narrower focus but greater feasibility of being solved. We might find that the problem is not ready to be solved and that we need to pause or cancel our product/service.

Reading: The Practitioner’s Guide to Product Management, Jock Busuttil

We can start looking for the right solution once we understand our problem, with the goal of achieving ‘product/solution fit’. The Design Council has famously used a ‘double diamond’ diagram to explain how we initially find problem/solution fit, and Jock Busuttil has refined it further.

Reading:

- The Design Process: What is the Double Diamond?, Design Council

- Find the tipping point in your research, Jock Busuttil

Our job as product managers is to work with our teams to continually optimise the value of our products and services - by ensuring that we keep and improve our problem/solution fit for our users - through the minimum, viable product possible. This is the goal of every iteration of our product/services. How do we do that?

We have some key tools that help us with our product strategy:

A problem statement should form the initial leap of faith for every product idea, then be refined and improved throughout the life of our products/services. Melanie Cannon from DWP has written helpful guidance on how to write a problem statement.

Value proposition, business model canvas, product vision, and product roadmap are some of the most critical strategic tools we use day to day:

- a value proposition is where our organisation's offer meets with our users' needs, explaining how our solutions fit with users' problems - a value proposition canvas is a tool that can help to create a value proposition

- a business model canvas describes how 'profitable' your value proposition is today, defining it in terms of value and cost - it looks at the overall operating model and helps us understand opportunities to optimise value - a business model canvas is a tool to help create a business model

- a product vision describes our goal in terms of the value of the product/service in the future - the estimated value the product will have in the future should justify the invesment of money, time and effort that we want to make - a product vision board is a tool to help us create a vision

- a product roadmap describes the steps needed to be taken from today (as described in the business model canvas) to the future (as described in the vision) - the roadmap makes promises to solve problems, not commitment to solutions or features - it is a flexible planning tool that should be reviewed and updated regularly as we learn more about our product/service

We should run a regular product strategy meeting to review all of the above (in addition to the teams more frequent sprint ceremonies).

Reading:

- Value proposition canvas, Strategyzer

- Business model canvas, Strategyzer

- Product vision board, Roman Pichler

- How to build product vision in 5 minutes, Ilya Leyrikh

- Product Roadmaps Relaunched, Todd Lombardo et al

- Roadmap principles, UK government product community

- Product roadmaps in 5 easy pieces, Scott Colfer

Training:

- Strategyzer workshops

- Product strategy and product roadmap, Roman Pichler

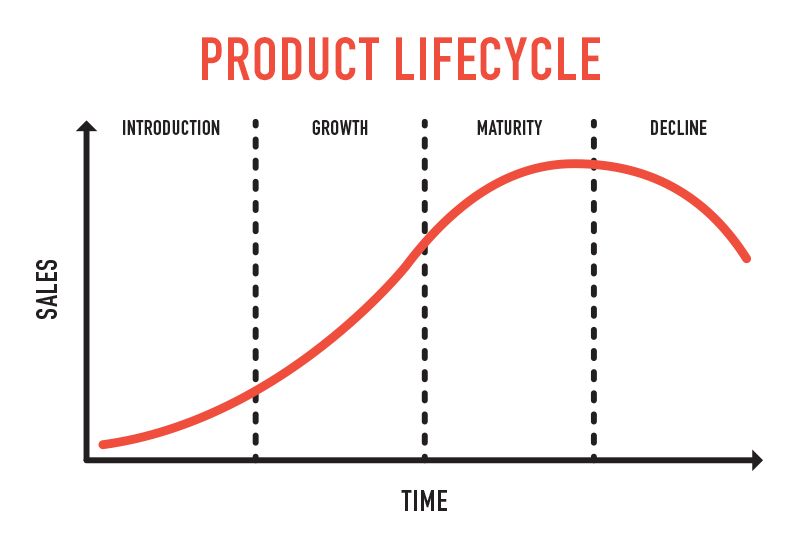

Our strategy will be strongly influenced by where our product is at in its lifecycle.

The above diagram is a standard description of a product lifecycle, and if you imagine that ‘sales’ is more likely to mean ‘adoption’ when working in government then it works for us. The GDS service standard takes us to somewhere around ‘introduction’ or early ‘growth’ but we often forget about the rest of the lifecycle:

- Introduction: initially, we’re looking to define the core features of our product in order to find problem/solution fit, so lots of the work will be focussed on development. As we get data that increases our confidence in the software’s features our focus will move to resilience (e.g. infrastructure, information security, service desk, etc) and the skills needed in our team will become more diverse.

- Growth: Once our service is resilient, our focus will be on increasing adoption. This may require marketing, communication, training and operational skills just as much as it requires development skills (maybe even more so).

- Maturity: Once our service approaches its maximum possible adoption then we look to optimise its value over time. New features is one aspect of this but we also need to prioritise innovation, service improvement, and technical debt.

- Decline: We need to review the vision, roadmap and business model canvas for our product/service throughout its lifecycle and at some point the value proposition will weaken to the point where the product/service should be retired. This may be because a business process or policy has changed significantly, a key technology has improved, a ‘competitor’ has a better offer (and lots of other reasons). Here we need to continue to meet the needs of users until they have moved to the new solution.

All of our work as product managers comes to life in the act of prioritisation. Our job is to lead our teams in prioritising the work that is most valuable. As we’ve seen in this guidance, value is context specific, depending on this like what problem we’re solving, who we’re solving it for, who our client is, and what stage of the product lifecycle we’re in. We can use the business model canvas to define what’s valuable today, our vision to define what’s valuable in the future, and our roadmaps to define what we think is valuable between now and then.

We can use data (often known as ‘metrics’) to measure value, set goals, and inform strategy - in other words, to help us prioritise our work. A lot is written about prioritisation but it’s still something of a ‘dark art’. Framing goals as hypotheses with pass/fail criteria helps us to bring more rigor to this process.

Reading:

- Product Prioritisation by the Numbers, Kate Bennet

- Deciding on priorities, GDS Service Manual

Here are a couple of tools we can use to get going with prioritisation:

- Prioritise today: impact vs effort is commonly used to evaluate options immediately in front of us. Here’s a guide to impact vs effort priorisation from Andy Wicks. Here’s a useful article called Why Prioritization by Impact/Effort Doesn’t Work by Itamar Gilad to help avoid some of the pitfalls of this approach.

- Prioritise over time: we will need to prioritise different types of work as our product matures. Here’s a guide to the different types of work required by a mature product from Barry Overeem.

Metrics (or data) is most useful when it leads to action. They should run through our vision, roadmap, business model canvas, and backlog. Metrics (or data) is most useful when it leads to action, e.g. it helps us to test a hypothesis about how to improve the value of our product/service, or helps us to prioritise an area for improvement. DWP has shared how they identified their key metrics for a service, and the GDS Service Standard contains a lot of advice on key performance indicators.