So it's been a while since I started this blog series on logging with Docker and though I said the next article will be about gelf and fluentd, I wanted to take the time to provide a more realistic example which illustrates what it takes to integrate logging into your web application. Because let's face it, this:

import sys

import time

while True:

sys.stderr.write('Error\n')

sys.stdout.write('All Good\n')

time.sleep(1)hardly counts as an application, nor you get paid for writing such code ;). That said we will create a very simple Flask application for creating Countdowns. The application code is already hosted on GitHub

The examples given throughout the article were created and tested using Docker v1.9.

How logging works:

- Anything your application write to it’s

stdin/stderrwill be shipped to the configured driver - Logging driver can be globally configured at the Docker daemon level, when launching it.

- When creating a new container one can specify the logging driver to be used, which effectively overrides de daemon's configuration.

As of Docker 1.9 there are 6 logging drivers implementations:

json-file: This is the default driver. Everything gets logged to a JSON-structured filesyslog: Ship logging information to a syslog serverjournald: Write log messages to journald (journald is a logging service which comes with systemd)gelf: Writes log messages to a GELF endpoint like Graylog or Logstashfluentd: Write log messages to fluentdawslogs: Amazon CloudWatch Logs logging driver for Docker

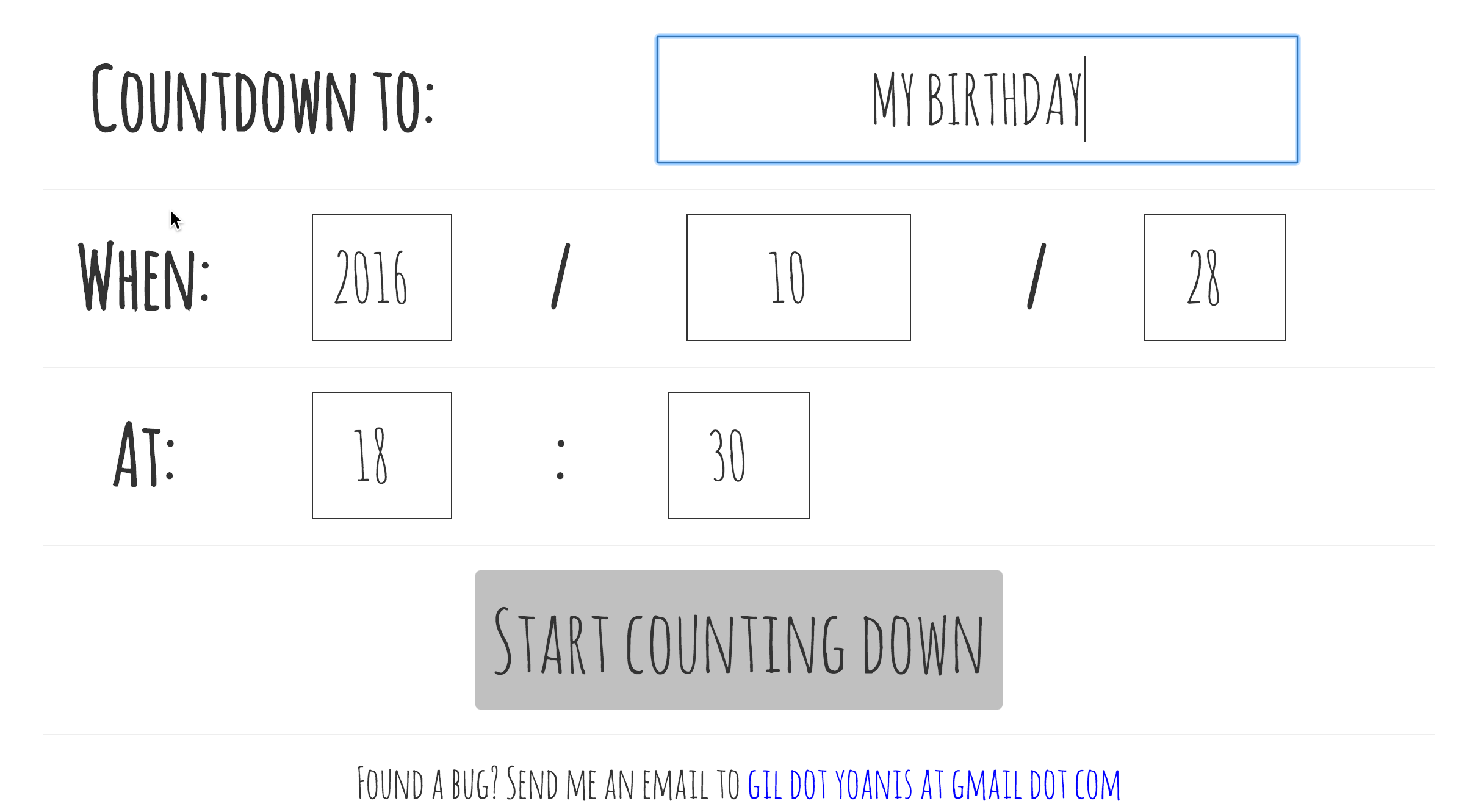

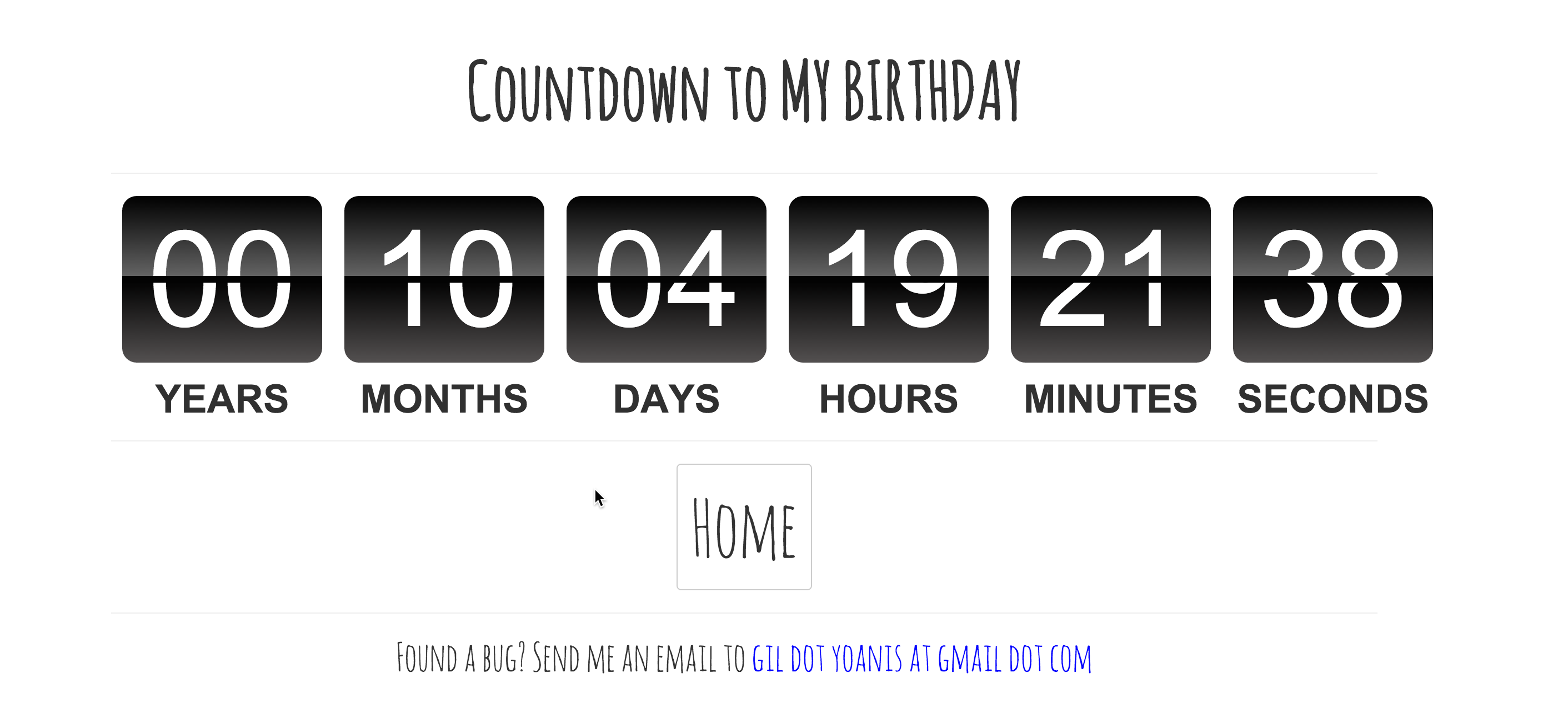

As stated before we will be using a countdown application for illustration purposes. The application is quite simple itself:

after providing a description for tracking down the time to your must beloved and anxiously awaited event you will be presented with:

Simple right? So let's get to work and break this thing in pieces.

As you might have already guessed this application was developed to work 100% with Docker so a Dockerfile has been created for that matter, which running a Python WSGI application using Nginx and Gunicorn. The file itself it's a quite a piece of work and it probably deserves it's own post (NOTE to self: Lets blog about it!). It's exactly 42 lines,I swear it was not my intention to do it like that, which takes care of:

- Installing Nginx.

- Installing application dependencies from

requirements.txt. - Providing a default Nginx site configuration which makes Nginx and Gunicorn work together.

- Providing a set of utility scripts to be able to launch the application from Gunicorn.

- Configure Supervisord to launch Nginx and Gunicorn.

If you take a closer look at the Dockerfile you will notice that the application entry point looks like this:

CMD ["supervisord", "-n", "-c", "/etc/supervisord/supervisord.conf"]

and this is because we're using Supervisord, a process control system, which acts as the Init Process. If you're wondering why a process control system like Supervisord is required, please take a look at this excellent article which explains the PID 1 zombie reaping problem.

Let's take a look at the life cycle of incoming requests to the application. Each HTTP request will follow the path below :

HTTP Request <---> Nginx <-- Proxy Pass --> Gunicorn <-- WSGI --> Flask Application

As we already know, the application needs to send all logging statements to it's stdin/stderr output but bear in mind that Docker will only collect the output from the process with ID 1. That said a few tweaks are required to Supervisord, Nginx and Gunicorn so that logging statements are transparently captured. Let's go over them.

Since we're using Supervisord to launch our application, this is where the Docker daemon will be collecting information from. We need to make sure that everything that get sends to Gunicorn/Nginx stdin/stderr output it's actually logged to Supervisord's stdin/stderr. Below the relevant pieces of configuration:

[program:gunicorn]

command=/usr/local/bin/gunicorn_start.sh

stdout_logfile=/dev/stdout

stdout_logfile_maxbytes=0

stderr_logfile=/dev/stderr

stderr_logfile_maxbytes=0

[program:nginx]

command=/usr/sbin/nginx

stdout_logfile=/dev/stdout

stdout_logfile_maxbytes=0

stderr_logfile=/dev/stderr

stderr_logfile_maxbytes=0

The important bit of config here is stdout_logfile=/dev/stdout and stderr_logfile=/dev/stderr since it instructs Supervisord to capture processes stdin/stderr output and forward it to Supervisord's stdin/stderr, which in turn will be collected by the Docker daemon and shipped to the configured logging driver.

Since supervisord collects stdin/stderr from the daemons it controls we need to instruct them to log everything to the expected descriptors. Bellow the relevants pieces of configuration for Nginx and Gunicorn:

####Nginx configuration

error_log /dev/stderr info;

daemon off;

events {

worker_connections 1024;

}

http {

...

access_log /dev/stdout main;

....

}

####Gunicorn configuration

exec gunicorn ${WSGI_MODULE}:${WSGI_APP} \

--name $NAME \

--workers $NUM_WORKERS \

--user=$USER --group=$GROUP \

--bind=unix:$SOCKFILE \

--log-level=info \

--log-file=/dev/stdout

With all the little pieces of configuration described above we can finally focus on logging from an application point of view. As example I've added a logging statement for each 404 error on the website:

@app.route('/v/<int:countdown_id>')

def countdown(countdown_id):

count_down = Countdown.query.filter_by(id=countdown_id).first()

if not count_down:

app.logger.error('404 on countdown with id %s' % countdown_id)

return render_template('404.html', countdown_id=countdown_id), 404

return render_template('countdown.html', countdown=count_down)

At this point it's really up to you to configure your Framework's logging handlers and make sure they log to stdin/stderr. In the case of Flask application there is already a logger object, which is a standard Python Logger object.

Back to our Countdown application, let's see it in action. To make things easier, I've crafted a Docker Compose file which will take care of building and running the application. After you clone the repo and before you launch the application make sure you edit the docker-compose.yml file and change the value of syslog-address to match your Docker setup. For instance if you're running Docker on OS X with Machine then you need to update this syslog-address: "udp://192.168.99.101:5514" to use the IP address of your virtual machine. With that in mind, let's launch the application:

$ docker-compose build countdown # Build the application image

$ docker-compose up -d countdown

$ docker exec rsyslog tail -f /var/log/messages

and then visit http://localhost:5000 and you should see the application welcome page. Let's force a 404 error by visiting http://dockerhost:5000/v/42. Go back to the console where the docker exec command was launched and you should see something like this:

2015-12-24T04:35:45Z default docker/countdown[1012]: -----------

2015-12-24T04:35:45Z default docker/countdown[1012]: ERROR in app [/srv/app/app.py:102]:

2015-12-24T04:35:45Z default docker/countdown[1012]: 404 on countdown with id 42

2015-12-24T04:35:45Z default docker/countdown[1012]: -----------

2015-12-24T04:35:45Z default docker/countdown[1012]: 192.168.99.1 - - [24/Dec/2015:04:35:45 +0000] "GET /v/42 HTTP/1.1" 404 394 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_10_5) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/47.0.2526.106 Safari/537.36" "-"

which shows a log statement from the application and from Nginx as well. How was this possible? Let's take a look at the Docker compose file:

countdown:

build: .

environment:

- NUM_WORKERS=1

- APP_NAME=countdown

- WSGI_MODULE=app

- WSGI_APP=app

- PYTHONPATH=/srv/app

- APP_LISTEN_ON=0.0.0.0

- APP_DEBUG=True

- PYTHONUNBUFFERED=1

- DB_DIR=/var/lib/countdown

ports:

- "5000:80/tcp"

volumes:

- ./data:/var/lib/countdown

links:

- syslog

log_driver: syslog

log_opt:

syslog-address: "udp://192.168.99.101:5514"

syslog-tag: "countdown"

syslog:

image: voxxit/rsyslog

ports:

- "5514:514/udp"

container_name: rsyslog

As you can see we're linking the container powering the Countdown application with the syslog container. This is not strictly required since it's the Docker daemon who takes care of forwarding logging output towards the syslog container, but it guarantees that the Syslog container is always started as a dependency of the application. The rest is the same, as it was covered on Part 1. We configure our container to use the syslog driver and we make sure to add a tag.

#What's next?

By now you should have a better idea about how to effectively let Docker capture your logging information without prior knowledge of your application architecture and have it send to a configurable backend.

The reason I like this approach is because of the degree of freedom it gives to both developers and sysadmins. Logging to stdin/stderr during the development process is a breeze since you don't need to tail/grep files located elsewhere. From a sysadmin/operations point of view it allows to easily configure how logging statements are archived, their destination, etc and most importantly without the need of performing any application specific configuration.

On the next article of these series I will finally approaching the fluentd, gelf and awslogsdrivers.