-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 20

Composition

Composition in GUI world is a hard nut to crack. Usually the focus is on visual elements (controls) composition while completely missing logic (Controller) composition, whereas the latter is the most valuable piece. Another approach is building black-box style UI components, which have logic encapsulated inside. But it is fundamentally flawed, because it is disconnected from the rest of event processing logic and therefore cannot be coordinated.

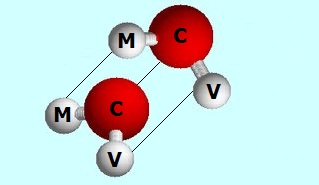

I always thought that MVC-triplets should make cohesive wholes by forming structure similar to the molecular composition: individual atoms connected to the counterparts of other MVC-triplets. This is a finer-grained form of composition.

As GUI framework WPF offers means only for visual elements composition. Let's look at it closely. I'm going to take a harsh stand on WPF controls "composability". There is XAML composability. Yes, for sure. Assuming XAML is a serialization format for WPF controls, serialized representation of controls is composable. One can argue that essential architecture supports composition. This may be true. But the fact is that it cannot be realized on API level. An attempt to compose controls in the code (C# or F# - it doesn't matter) still looks like an old stinky imperative logic. All I'm trying to say is that composition is not a first-class concept in WPF. It was a real surprise to find out that Anders Hejlsberg is unaware of the problem. That said it still doesn't make sense to fight WPF, but rather find a reasonable way to get along.

The sample calculator application as we left it in [previous chapter](Reentrancy Problem) looks messy. It has everything on one screen: calculator, temperature converter and stock prices chart. It would be nice to have them visually separated. But we'll take it even one step further - factoring out those as separate components (MVC-triples). We will add extra functionality - main window title is going to show current process name and active tab.

Each individual component now has its own Model:

...

type CalculatorModel() =

inherit Model()

abstract AvailableOperations : Operations[] with get, set

abstract SelectedOperation : Operations with get, set

abstract X : int with get, set

abstract Y : int with get, set

abstract Result : int with get, set

...

type TempConveterModel() =

inherit Model()

abstract Celsius : float with get, set

abstract Fahrenheit : float with get, set

abstract ResponseStatus : string with get, set

abstract Delay : int with get, set

...

type StockPricesChartModel() =

inherit Model()

abstract StockPrices : ObservableCollection<string * decimal> with get, setComposition of the model is as simple as declaring of the composite data structure. This is the result of defining model as a declarative data structure without complex logic attached to it.

type MainModel() =

inherit Model()

abstract Calculator : CalculatorModel with get, set

abstract TempConveter : TempConveterModel with get, set

abstract StockPricesChart : StockPricesChartModel with get, set

abstract ProcessName : string with get, set

abstract ActiveTab : string with get, setNotice that MainModel has both composite part and its own state (ProcessName and ActiveTab).

UserControls is THE way to archive composition/reuse in XAML. CalculatorControl.xaml, TempConveterControl.xaml and StockPricesChartControl.xaml are factored-out XAML parts. XAML-composition is done through standard technique (look for Example/XAML section).

CalculatorControl.xaml:

<UserControl x:Class="FSharp.Windows.UIElements.CalculatorControl"

...>TempConveterControl.xaml:

<UserControl x:Class="FSharp.Windows.UIElements.TempConveterControl"

...>StockPricesChartControl.xaml

<UserControl x:Class="FSharp.Windows.UIElements.StockPricesChartControl"

...>MainWindow.xaml:

<Window x:Class="FSharp.Windows.UIElements.MainWindow"

...

xmlns:local="clr-namespace:FSharp.Windows.UIElements"

...>

...

<TabControl>

<TabItem Header="Calculator">

<local:CalculatorControl x:Name="Calculator" x:FieldModifier="public"/>

</TabItem>

<TabItem Header="Async Temperature Converter">

<local:TempConveterControl x:Name="TempConveterControl" x:FieldModifier="public"/>

</TabItem>

<TabItem Header="Stock Prices">

<local:StockPricesChartControl x:Name="StockPricesChart" x:FieldModifier="public"/>

</TabItem>

</TabControl>

...See MSDN and other sources for detailed coverage of UserControls. Notice that child controls are declared with Name and FieldModifier attributes in order to force generation of statically typed accessors. An alternative is to use dynamic lookup operator defined on the base View class.

Capabilities to show/close window that we added to the view in Child Windows chapter are specific to full view. Because reusable controls are always hosted inside parent view they cannot carry this functionality. This means we need to split IView interface:

type IPartialView<'Events, 'Model> =

inherit IObservable<'Events>

abstract SetBindings : 'Model -> unit

type IView<'Events, 'Model> =

inherit IPartialView<'Events, 'Model>

abstract ShowDialog : unit -> bool

abstract Show : unit -> Async<bool>In order to be pluggable into bigger Window-based View it's enough for a view to implement IPartialView. Base View classes now reflect the change:

type PartialView<'Events, 'Model, 'Control when 'Control :> FrameworkElement>(control : 'Control) =

member this.Control = control

static member (?) (view : PartialView<'Events, 'Model, 'Control>, name) =

...

interface IPartialView<'Events, 'Model> with

member this.Subscribe observer = ...

member this.SetBindings model = ...

...

abstract EventStreams : IObservable<'Events> list

abstract SetBindings : 'Model -> unit

[<AbstractClass>]

type View<'Events, 'Model, 'Window when 'Window :> Window and 'Window : (new : unit -> 'Window)>(?window) =

inherit PartialView<'Events, 'Model, 'Window>(control = defaultArg window (new 'Window()))

...

interface IView<'Events, 'Model> with

member this.ShowDialog() = ...

member this.Show() = ...Individual views are descendants of PartialView.

type CalculatorEvents =

| Calculate

| Clear

| Hex1

| Hex2

| YChanged of string

type CalculatorView(control) =

inherit PartialView<CalculatorEvents, CalculatorModel, CalculatorControl>(control)

...

type TempConveterEvents =

| CelsiusToFahrenheit

| FahrenheitToCelsius

| CancelAsync

type TempConveterView(control) =

inherit PartialView<TempConveterEvents, TempConveterModel, TempConveterControl>(control)

...

type StockPricesChartView(control) as this =

inherit PartialView<unit, StockPricesChartModel, StockPricesChartControl>(control)

...Not very interesting, as all of them are just a result of simple decomposition of previously monolithic view. MainView deserves more attention though:

type MainEvents = ActiveTabChanged of string

type MainView() =

inherit View<MainEvents, MainModel, MainWindow>()

override this.EventStreams =

[

this.Control.Tabs.SelectionChanged |> Observable.map(fun _ ->

let activeTab : TabItem = unbox this.Control.Tabs.SelectedItem

let header = string activeTab.Header

ActiveTabChanged header)

]

override this.SetBindings model =

let titleBinding = MultiBinding(StringFormat = "{0} - {1}")

titleBinding.Bindings.Add <| Binding("ProcessName")

titleBinding.Bindings.Add <| Binding("ActiveTab")

this.Control.SetBinding(Window.TitleProperty, titleBinding) |> ignore Nowhere MainView concerns itself with composition logic. We'll see later how it is actually composed with child views. There are also some new challenges (for example, support for StringFormat property) that our data binding doesn't know how to cope with. [upcoming chapter](Data Binding. Growing Micro DSL) will address this and many other data binding-related issues.

Finally, we have arrived to the most critical piece of composition puzzle - controllers. Before we move on let's look at MainController:

type MainController() =

inherit Controller<MainEvents, MainModel>()

override this.InitModel model =

model.ProcessName <- Process.GetCurrentProcess().ProcessName

model.ActiveTab <- "Calculator"

model.Calculator <- Model.Create()

model.TempConveter <- Model.Create()

model.StockPricesChart <- Model.Create()

override this.Dispatcher = function

| ActiveTabChanged header -> Sync <| this.ActiveTabChanged header

member this.ActiveTabChanged header model =

model.ActiveTab <- header- Inside

InitModelcontroller has to take care of creating child models in addition to initializing its own model. - Similar to

MainView, other than the bullet point above,MainControlleris not exposed to the composition logic in any way - it only takes care of its own stuff. Updating main title with current process name and active tab could be done purely through the data binding, but I wanted to demonstrate that parent controller can have its own event handling.

All child controllers (CalculatorController, TempConveterController, StockPricesChartController) are the result of a very straightforward decomposition. So, I won't bother showing code here, please look at the accompanying source code for more details.

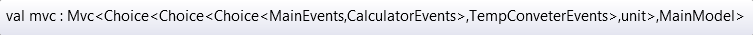

Now I'm going to show how final controllers composition logic looks like. Ladies and gents, fasten your seat belts. Here we go:

[<STAThread>]

do

let view = MainView()

let mvc =

Mvc(MainModel.Create(), view, MainController())

<+> (CalculatorController(), CalculatorView(view.Control.Calculator), fun m -> m.Calculator)

<+> (TempConveterController(), TempConveterView(view.Control.TempConveterControl), fun m -> m.TempConveter)

<+> (StockPricesChartController(), StockPricesChartView(view.Control.StockPricesChart), fun m -> m.StockPricesChart)

mvc.StartDialog() |> ignoreLet's go step by step through controller's composition implementation.

Operator <+> is a synonym for Mvc.Compose method:

type Mvc...

...

static member (<+>) (mvc : Mvc<_, _>, (childController, childView, childModelSelector)) =

mvc.Compose(childController, childView, childModelSelector)So, the composing logic could be written as well as :

...

let view = MainView()

let mvc =

Mvc(MainModel.Create(), view, MainController())

.Compose(CalculatorController(), CalculatorView(view.Control.Calculator), fun m -> m.Calculator)

.Compose(TempConveterController(), TempConveterView(view.Control.TempConveterControl), fun m -> m.TempConveter)

.Compose(StockPricesChartController(), StockPricesChartView(view.Control.StockPricesChart), fun m -> m.StockPricesChart)

...Method declaration:

...

type Mvc ... =

...

member this.Compose(childController : IController<'EX, 'MX>, childView : IPartialView<'EX, 'MX>, childModelSelector : _ -> 'MX) =

...Several key points from the example above:

- Composition result is yet another

Mvc. Formally speaking, it satisfies a [closure property](http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Closure_(mathematics\)) – an important composability facilitator. - Right-hand side of

<+>orComposeis a child MVC-triple, but instead of model instance a model selector is expected that pulls a child model out of bigger composite.

Let's dig into Mvc.Compose implementation:

type Mvc... =

...

member this.Compose(childController : IController<'EX, 'MX>, childView : IPartialView<'EX, 'MX>, childModelSelector : _ -> 'MX) =

let compositeView = {

new IView<_, _> with

member __.Subscribe observer = (Observable.unify view childView).Subscribe(observer)

member __.SetBindings model =

view.SetBindings model

model |> childModelSelector |> childView.SetBindings

member __.Show() = view.Show()

member __.ShowDialog() = view.ShowDialog()

}

let compositeController = {

new IController<_, _> with

member __.InitModel model =

controller.InitModel model

model |> childModelSelector |> childController.InitModel

member __.Dispatcher = function

| Choice1Of2 e -> controller.Dispatcher e

| Choice2Of2 e ->

match childController.Dispatcher e with

| Sync handler -> Sync(childModelSelector >> handler)

| Async handler -> Async(childModelSelector >> handler)

}

Mvc(model, compositeView, compositeController)Mvc.Compose makes views composition first. Composing views mostly means composing event sources. New Observable.unify function performs exactly this. Pay attention to the type signature - it will help you to get a better intuition into what it does exactly.

The idea is similar to events mapping we do manually to implement EventsStreams property on View. Here though it can be automated, because the mapping is unambiguous. Target DU type is Choice<'T1,'T2>.

View composition leverages Observable.unify method to compose event source and delegates SetBindings calls to parent and child views. Show, ShowDialog and Close are straightforward delegations to parent. Parent must be IView, not IPartialView. In WPF terms it means controls can be hosted inside Window, not vice versa. childModelSelector parameter has the exact same meaning as in controller's composition.

After two views are combined, the method build composite controller. First InitModel calls parent, then child controller. That's why we can say that parent controller is aware of composition (suppose to build composite model by creating child models and assigning them to respective properties), but does not deal with low level details of it. Dispatch function redirects an event to the proper controller - either parent or child. And all these goodies are statically type-proved by compiler.

Several F# language features were essential to make the composition feature implementation/usage sensible: object expressions, wildcards as type arguments and especially type inference. For example, just imagine how tedious it would be to provide type for resulting controller in our sample application by hand-coding:

In AsyncController chapter we have introduced a specialized SyncController to address common pattern in application where controller has sync event handlers only.

[<AbstractClass>]

type SyncController<'Events, 'Model>(view) =

inherit Controller<'Events, 'Model>()

abstract Dispatcher : ('Events -> 'Model -> unit)

override this.Dispatcher = fun e -> Sync(this.Dispatcher e)Sub-typing is rather tight coupling and this smells. The problem could be nicely solved by using constructions like mixins. Unfortunately, F# language doesn't support mixins, as some other popular these days languages do.

Luckily, there is an elegant F# solution. Here is an excerpt from CalculatorController:

type CalculatorController() =

inherit Controller<CalculatorEvents, CalculatorModel>()

...

override this.Dispatcher = Sync << function

| Calculate -> this.Calculate

| Clear -> this.InitModel

| Hex1 -> this.Hex1

| Hex2 -> this.Hex2

| YChanged text -> this.YChanged textNotice how the choice of making Dispatcher a high-order function pays off. Would could not archive that much with a plain .NET method (F# class member).